af Christian Skeel

Mainstream was born out of coincidence. From 1984 to 1986 I used the sequencer pro24, the forerunner of Cubase, for making music, together with an 8-track Tascam tape recorder and an Akai S900 sampler, all in a small studio in my apartment.

I had no idea concerning what went on in the world of film. However, my downstairs neighbour was a sound editor student at the Danish Film School, and he was genuinely interested in my machines. I demonstrated for him the flexibility of the combination of the sequencer and the tape recorder, and this made him ask whether it would be possible to use this technique for making film soundtracks.

I became curious and wanted to find out what it would take to make it work. It turned out that there were a lot of problems; in the first place, the 12-bit sampler did not offer quality at film level, and secondly, there was no way in which computer and flatbed editors or MVA-tape recorders could be synchronized. Furthermore, the Tascam tape recorder needed effective noise reduction. All this did not exist at the time.

In spite of the utopian nature of the entire project, I started the Mainstream company in 1987. For me, it was unimaginable that this was not going to be the future, so I was blind to the obstacles.

The name Mainstream came from a desire to create a workshop for everyone interested in working with sound.

Such visions were not realistic in the confines of the apartment. I had some childhood friends who had built the sound studio Easy Sound in the Triangel movie theatre, and they let me rent the Studio 3 in the movie theatre basement. I had followed the establishment of Easy Sound closely for 10 years and had learned a lot about what could be done and not least how to do it. My old friends were an enormous help to me.

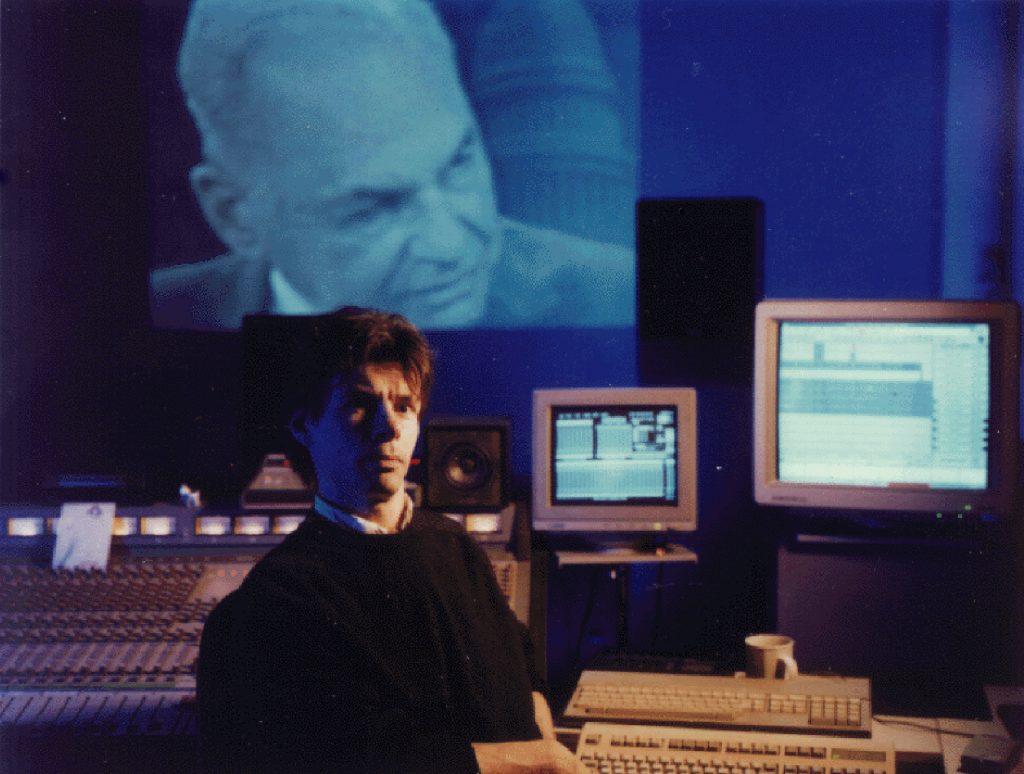

There was plenty of room in the basement, but it was low-ceilinged and placed deep down underneath the cinema. Actors and directors heading for the studio always looked quite anxious once they found out where they were going. As may be seen in the photos, I was the guy with the quick do-it-yourself solutions when it came to setting up the machines. That cannot have seemed terribly reassuring.

At the time I had a hard disk with a defective magnet. Thus, once my customers were sitting down, I had to climb on all fours in order to insert a screwdriver into a ventilation hole in the hard disk cabinet and slap the hard disk into rotation. The director sighed with relief when the first sounds emerged from the speakers.

At the time, all machine connections were cabled and very little was happening in the computers. This cable mess constituted challenges of its own. There was always something humming, or something which had the wrong entry level. Or the wrong pin went hot in a plug, due to the fact that Europe and the US used different standards. Everything needed to be grounded properly, which was an impossible task since all machines and appliances were constantly plugged in and out of a patch bay in order to be reconfigured in a new way.

For instance, WaveFrame, my system for hard disk editing, always needed at least one plug to be connected to the patch bay. If everything was unplugged, the switchboard would cut off the current, leaving everything pitch black when the first machine was plugged in, because of the potential difference between the machines.

When I forgot about this, especially when customers were present, the switchboard would cut off the current and everything would go pitch black – only the scared faces of the customers would seem to light up in the room. I switched on a battery torch which I always kept there for the occasion, and I would maintain that is was due to a minor power cut while I fumbled to turn off all the machines, turn on the switchboard, and switch on all the machines again and in the right order.

In the course of the next 3 years, both came an Akai 16-bit sampler and a machine for synchronizing the sequencer with the tape recorder via SMPTE code. The code itself was recorded on one track of the tape recorder and then sent directly to the sequencer in the computer.

This procedure introduced the kind of problems that were to be part of my life for the next 15 years.

A SMPTE code is so noisy that it bleeds to both neighbouring tracks and the tape on the reel before and after. Thus the SMPTE code had to be recorded at a very low level, and the tape had to be wound up backwards, so that the bleed was on top of the other sounds rather than in front of them.

Little by little, as I ventured further and further into the construction of the studios, this kind of puzzle grew rapidly.

I made a VHS tape recorder emit capstan information (speed), which I was then able to send to the Tascam’s sync port, enabling me to run the sounds in the sequencer in sync with the picture.

At some point, hard disk recording had been invented. This proved exciting because it made direct sound recording to the computer possible, and it made it much easier to move sounds around and trim them. However, the drawback of the method was that there was still no way to sync picture and computer, i.e., without tape there could be no sync.

At the time, there was no solution to this problem, but I discovered that the clocks of the video recorder and computer were close enough together for me to hold the sync for 10-15 minutes. I therefore for some time worked without synchronisation between video and computer as I knew that my master would later be transferable to perf (perforated magnetic tape) and attached to the film and still be in sync. This method proved slightly problematic at screenings, as I intended to play films with sound as if everything was synced. I parked the computer next to the blob right before the first frame, a visual number 3. I was ready to press enter on the computer, so that the blob started on the number 3. If I did not succeed in doing this, I had to apologize and try again. In no way could I admit that sound and picture were not in sync, as there were enormous doubts about digital sound.

I knew that some kind of synchronization apparatus had to surface sooner or later, so I held my breath and continued with my homemade system.

The criticism of digital sound was comical because instead of pinpointing (as I had feared) the deficiencies of digital sound (and they were there), digital sound was accused of all sorts of things, from having lost the atmospheres to having made the dialog out of sync at random. Therefore I did some demonstrations during which I asked sceptics of the field to guess which sounds were digital and which were analogue. As the analogue machines had some noise, alongside with the digital track I played a separate channel with tape hiss, so that the amount of noise was the same. Of course no one could hear what was analogue and what was digital. Shortly after I started teaching digital sound editing at the Film School. I knew that it was important to make the people of the trade feel familiar with digital sound as early as possible. Likewise, it was important that as many sound editors as possible were able to operate similar systems, so that we did not end up with a situation where each sound editor was able to only work with different types of machines.

Finally, a method for synchronizing sound and picture was developed, using a new type of code called VITC. This was possibly even more difficult to work with than SMPTE. It had to be embedded in video picture frames outside of the visible picture area. Thus the initial problem involved was making the film labs understand how to do it. It failed every time, and in most cases I had to go to the lab myself to help make everything work.

At Danmarks Radio it was not possible at all, so when films came from there, I had to find a lab that was willing to help. Often it took ages to simply create a usable copy. You have to remember that everyone in the sound trade were more than willing to knock out digital sound, so what mattered was to make everything seem problem free. If not, no producer would touch digital sound at all.

What attracted customers was the fact that I was able to offer an unheard of level of flexibility in the editing process; much more so than was the case in normal flatbed editors, plus the fact that I was able to do it at a much lower price than the film studios. Then, as now, there were a lot of ideas for films, but no money, so someone was always hunting for cheap workshops.

When I discovered that Danmarks Radio had the funds to send people around the world so that they could study the very latest technologies, I managed to make myself interesting to them. I knew that I would have to invest in a computer system dedicated to film editing, and DR had come to the conclusion that the American company WaveFrame was best. DR bought a number

of systems for themselves, so my idea was that if I had problems with a system like that, there would always be skilled people to ask for advice and perhaps even spare parts. I therefore took a loan in my father’s house, crossing my fingers that he would not end up being thrown onto the street, and with that money I bought a WaveFrame system. When the system arrived, it did not work; I was not even able to turn it on. After a couple of weeks with a repair man, the computer came to life, but there was no way in which I could synchronize it to the codes I normally used. I found out that the reason was that the system was solely aimed at sync’ing with Sony’s professional Betacam machines, which I would never be able to afford. It took a year before we succeeded in synchronizing the WaveFrame and the picture, not to mention the toll it took on my nervous system.

WaveFrame had the best backup system of the day, using a special type of video tapes in an expensive specialized drive. Hard disks cost a fortune, and the largest had a capacity of 320 megabytes. They took up a lot of room and were noisy, so it was necessary to keep them in a separate room. At the time, cables between computer and hard disk were max 30 – 40 centimetres long, and thus methods had to be found to make the cables long enough for the disks to be located in another room.

I had to empty the disks whenever I had an hour’s worth of recordings, as that was what my hard disk capacity would allow. I therefore made a tape backup, erased the hard disks, and started over. If I wanted to return to an earlier backup, I had to back up what was on the disk, erase the hard disks, and load the old tapes. This could have been simple, but of course the backup tapes never worked. Normally, WaveFrame would back up a project without errors, but the loading of a backup almost always went wrong.

This meant that the first thing that met me every morning was ‘load error’. As a consequence I went to work very early in order to attempt another reload. I always succeeded, but more often than not I had a sweaty forehead even before the first customers arrived.

As a result, I began making double backups of everything while at the same time transferring the material to reel-to-reel tapes, just for safety. This procedure saved me time and time again. But the workload wore me down, as I was at work around the clock, seven days a week.

One day Fortuna Film expressed an interest in finding out whether I would like to help them with some feature film effects.

Being allowed to use digitally produced sounds in a feature film might be what would change the attitude of the trade towards digital sound, so I felt really motivated.

The owner of Fortuna Film was Peter Ålbæk, and the director was the photographer Tom Elling. Soon I found out that the film budget was quite low and the mood high, so they stayed, and in the following year I expanded as quickly as the film required. You might say that this particular film was what made Mainstream ready for the production of film sound. Ålbæk became the producer for Lars von Trier’s Europa and placed part of the effects work with me.

I had outgrown the basement and was in need for a new place for my studio. Some excellent rooms in nearby Ryesgade proved to be for rent.

So I rented the entire ground floor: 800 m2, or around 700 more than I needed. Therefore I invited small film producers to rent rooms from me, thinking that this might get them used to the digital world, experiencing it at close range on an everyday basis. Peter Ålbæk was first to move in, with his Fortuna Film, and shortly after with von Trier and their new company Zentropa.

At some point I realized that I would no longer be able to run the studio on my own. Some time before I had met Hans Møller, who seemed to be in possession of everything I needed, so I asked him if he would like to join me. He was keen, and we decided that Hans would be working as supervising sound editor, while I took care of development and whatever it entailed at the time. That was quite a relief, although I still had to fight backups that would not load, as well as all the other problems.

The first project of our cooperation was Jens Jørgen Thorsen’s film about Jesus. In the beginning everything went according to plan. As was always the case, I was working both night and day, while Hans was the sound supervisor and kept Thorsen satisfied.

But, as the work with the sound progressed, and the film premiere drew closer, Thorsen got more and more nervous and started doubting whether we could be trusted. He visited time and time again to check every single sound we had produced for the film. At the same time, the WaveFrame system had started to drop files in random places. Occasionally they appeared again in places where they did not belong. I gave up sleep altogether and stayed by the system for weeks, until one day when my nervous system collapsed. After that I realized that I would not be able to untie more knots, although I might be of use for basic tasks. From then on Hans took over, we dropped the use of the WaveFrame and used the Tascam backups for the mixing. Fortunately, Hans remained completely calm, at least as seen from the outside, and he was able to carry out the project with a successful mix. In short, he saved us from crashing completely.

I knew that we had to add another hand, this time preferably someone with the skills necessary for participating in the tech department. Prior to working with me, Hans had co-owned a studio, Humdrum, with Eddie Simonsen, a friend of his, so Hans asked me if I agreed that we could ask him. I okayed to give it a shot for a while. Eddie and I got along really well from the start, and not long after he suggested that he could close Humdrum and move his gear in with us. That way we could have another full studio.

It turned out that Eddie shared my love for and curiosity concerning development, so we slipped into a kind of symbiosis in which we lived and breathed for the studios day and night. We took our meals together every day, and as if that was not enough, we hung out together afterwards, until we were due back at work. I had got myself a twin.

Where I normally lost energy when plans and ideas were to be carried out, Eddie became hyperactive and with what to me seemed like groundbreaking courage engaged in taking apart various machines in order to modify and rebuild.

Together we were able to speed up development considerably, and the more we built, the more energy we were able to invest. What had looked like a company with no more than two studios, suddenly developed into one with seven studios and a mix stage.

During this developmental tornado we found out that we needed a proper engineer, given the fact that the systems grew in complexity. From my time at Easy Sound I knew Olivier Richter, who was not only an excellent engineer, but also a fine human being and a good friend. I asked him if he could spare a little time to help us sometimes, and his answer was ‘no problem’. Soon Olivier became the central nervous system of everything technical in the studios, and as had been the case with Eddie, Olivier soon moved in in Ryesgade.

The four of us spent several happy years enjoying our close friendship and a fabulous ability to develop and run the studios.

Our quartet proved to be the essential factor in the running of the studios through those impossible pioneering years. Around 2000 we moved to the film centre in Hvidovre. The pioneering days were over, and I no longer had anything to do there, so I left the studios. Luckily, they are doing really well without me.

However, the friendship and desire to develop something together is not over yet. New and glorious horizons await.

Christian Skeel